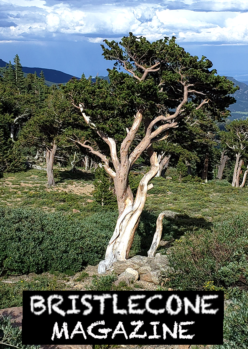

Photo by Sandra S. McRae

Poems by

Beth Franklin, Erica Hoffmeister, Karla Johnson,

Marcia Jones, Donald Levering, Jessy Randall, and Tim Raphael

© 2023 Bristlecone

SUBMISSION GUIDELINES

Bristlecone welcomes poems from writers of the Mountain West region. The editors are especially eager to read poems that reflect the region’s various cultures and landscapes, although we have no restrictions in mind regarding subject matter. Our main concerns are with the quality of the work and the cultivation of a regional community of poets and poetry lovers.

Submissions are accepted year-round. Please adhere to all of the following guidelines:

- Submit 3 to 5 unpublished poems in a single Word attachment (no poems in the body of an email) to: editors@bristleconemag.com. Submissions with more than 5 poems will not be considered.

- Poems posted on blogs and social media are considered published. Simultaneous submissions are fine as long as you let us know right away if the work is accepted elsewhere.

- Use a header on at least the first page of your submission that includes your:

- Name as you wish it to appear in the journal

- Mailing address

- Email address

- Phone number

- Website address (if you have one)

- Phone number

- Submission should be in .doc or .docx file format (no .rtf or .pdf)

- Times New Roman 12 pt. font—titles in bold and not all caps

- Flush left alignment except for drop-lines, internal spaces within lines, and any other special formatting your poem requires

- 100-word maximum bio at the end of the submission; same guideline for translator bio(s). Feel free to provide live links to your website.

After publication, all rights revert to the individual Bristlecone authors. We consider simultaneous submissions but please let us know immediately if something you’ve submitted to us has been accepted elsewhere.

The Editors: Joseph Hutchison, Jim Keller, Sandra S. McRae, and Murray Moulding

Beth Franklin

Ghazal in the Land of Love

In the land of love, my heart got broken,

seven times seven times seven every time.

Scarlet dinner-plate hibiscus, one day alive,

droop, fall to the ground, at evening time.

Stones placed over daughter bones, press mother

and grandmother bones, marking ancestral time.

Worn out typewriter keys craft poem

after poem, beating wildly to love time.

La Malinche, indigenous traitor from pre-colonial time,

transforms to hero, Chicana icon, in post-colonial time.

A wheelchair, four walkers, a radiation mask upside down

on a garage hook, prolong mourning time.

A framed photograph, the groom’s gray tweed suit,

the bride’s white pleated dress, begin a lifetime.

Orange slices, delicately arranged on a blue plate,

first painted with watercolor, then eaten one at a time.

A thin mattress from the hospice bed, tossed

into a red dumpster; a breath taken. Last time.

“A Throw of the Dice”

This last time,

I walk around the ponds a few blocks

from our house, sold and empty.

Until today, a walk taken daily.

A bald eagle rests high on a cottonwood branch,

in undergrowth, geese surround their goslings, protective.

A gray heron, hidden among cattails, stands rigid.

Red-winged blackbirds balance, trilling, on single stalks.

Did you know he smoked waiting for you?

What did you think would happen when you married an older man?

Why are you always with other widows?

The snow dustings on the iced-over ponds invent geometric patterns.

Rabbitbrush sleeps, not yet its late summer yellow.

Fields of blue flax will flower to the left of the path.

Serviceberry, with withered fruit clusters, will bloom purple in June.

I carry my father’s prayer card,

the last line from the Irish blessing soothes:

Until we meet again may God hold you

in the hollow of his hand.

You, drum major extraordinaire,

melodious voice on the human stage of poetry

swing dancer, jiver, string bass jazz musician.

And the quiet you, gazer of trees, rocks and rivers.

Bagpipes. Heard that first time in an Inverness bar.

We stood with the raucous Scottish crowd singing

their beloved Anthem, music played at your final

Celebration of Life.

A photo taken by my oldest friend forty years ago—gifted to me

when she came to say a final goodbye—shows me reading

Mallarme’s “A Throw of the Dice.” Blossoms are

everywhere on my walk.

Why do you write about cancer?

Why do you paint yellow coneflowers on the edge of the river

at the cabin?

Sometimes a Beauty, Sometimes a Beast

“Ask the wild bees what the Druids knew.”

—Anonymous

When my mother died, they found

an aerogram written to my Irish-American

grandmother. 20, in Madrid, writing

about discothèque dancing with Spanish

architecture students late into the night,

learning a lot, nice people, thanks for the $10.

A clipping from the Indy Star, quotes me—

Purdue co-ed—questioning her American culture

and values. Aerogram and newspaper clipping,

saved evidence of a mother’s and grandmother’s

pride for a young woman who left home

for distant adventures.

My seven-year-old niece, a Halloween Disney Belle,

revels in her floor-length yellow satin dress,

jeweled tiara, matching gloves, sparkling earrings.

With her mother’s makeup in hand, she requests

a heart crown painted on her forehead. Now tattooed,

the young princess waltzes through the living room.

I paint a watercolor of a green apple with two leaves

casting a shadow on the journal page. I feel

the rounded apple in my body. My dancing niece

grabs the gymnastic rings hanging from the kitchen

ceiling, her backflip turning her princess dress

inside out. Eating an apple, I watch her.

She tells me she loves apples, sliced thin as wafers.

With a somersault she gains momentum,

pausing midair, legs straight up.

Beth Franklin, poet, painter, is the Executive Director of the Colorado Poets Center. In her role as Director, Franklin coordinates and sponsors in-person and virtual poetry readings; the Robert W. King Poetry Prize, a yearly contest for the high school students in the Greeley-Evans School District 6; and publishes The Colorado Poet newsletter. She is professor emerita at the University of Northern Colorado, where she prepared pre-service teachers in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Education. A passionate believer in the importance of poetry, Franklin is dedicated to developing and supporting local and global poetry projects. She lives in Boulder, Colorado.

Erica Hoffmeister

Dandelion Heart

I want one-hundred legs

instead of these unreliable two.

A centipede in its stop-sudden mirage of fright

landscaping dandelions for what they are: resilient

medicinal, caught between concrete domesticity and

rebellion entrenched in slow-moving ferality.

I want to be a horror show: my body

amazing in the most traditional definition.

Flowing in rhythmic patterns, tidal, near-

villainous, terrifying those in my path

simply by moving in my strange, alien

existence, earthly existence, scurrying

and parting waves of humanity in my wake

over pavement, through small gardens and

damp soil.

I wonder where centipedes go after the march of terror

commences. I wonder if their families hug with two legs,

or all one hundred. If, like my mother, who needs

all parts of her body to love, they

smother their children with one-hundred

little feet, or hands, or whatever limbs

attach themselves to sectional parts of entity.

My two legs that carry this body: my inability

to move my segments in sync—my self

always twisting from its center, limbs flailing

against harsh concrete, man-

made obstructions.

Horror show, dandelion heart. Ordinary.

Someone always mistaking me for a weed.best laid plans

This is not a poem about the sweet scent of orange blossoms

drifting through bright blue skies of childhood memory,

the soft-petaled magnolia leaves, my mother’s jasmine

This is not about the ocean’s whisper, my salt-stuck curls

or the best breakfast burrito in town

This is not about my appendages ripped from their sockets

and tossed into farther corners of once-possibility, my torso

held hostage against Colorado’s snow drifts

my teenage-era locked door, my mother and I’s shared room,

a year spent mostly sprawled across my best friend’s sofa,

her legs translucent white

This is a poem about a hallway always occupied, the soothing hum

of chaos, park birthday parties filled with cousin-limbs and sibling

jokes: that time my brother drank too much on Halloween, my sisters’ twin giggles,

a knife always at her hip to heat and cauterize my open wounds

my nephew’s curly blonde hair, my mother’s wisdom, a double helix blue

and citrus wax candle to light when this mountain range partition

annexes our connected sky, a tiny flame

held against my chest’s permafrost

It’s when I say that Las Vegas is my favorite city, remember glass shards

sparkling in the street, hands splayed out of fast-driving windows

under a sky that cracks open on a regular Monday morning.

I sprout citrus appendages on tilled soil, a beautiful comeback, an

unremarkable origin story

This is a poem about truth-dreams that ache my bones each night

at 4am, awaken and descend into a disorienting free dive,

the conversation I never had with my husband

hallucinating desert depths

A cataclysmic variable—

binary star systems that merge and rotate into

a death spiral until they explode and die

they must exist together

or not at all

Erica Hoffmeister is a rambling soul from Southern California who now lives in Denver, where she teaches college writing. She is the author of two poetry collections: Lived in Bars (Stubborn Mule Press, 2019) and Roots Grew Wild (Kingdoms in the Wild Press, 2019), but considers herself a cross-genre writer. Learn more at www.ericahoffmeister.com.

Karla Johnson

Gertrude’s Maid

Maid had sloughed out of her starched

white manners

white cleanin costume and

white-world stance of

high alert watchin

Babys’ heads were pressed

dresses unmessed

curlers set

so the mornin’s style could be

blessed and ready to bear sweat

in worship tomorrow.

Maid’s now home with

sisters at the table tappin

whist cards slappin

raucous freedom boomin

through lit cigs on lips, smoke curlin

up, a cloud of relief from the day.

Sisters were knowin

how washerwomen

got recruited

to be witnessin

the Nordic antics

of the dirtied white rooms of

gained wages.

Sisters at the table

demandin

of Maid

wait she said what

hold up she made you listen to what

naw what

sisters hopin

for a story from the famous woman’s lair.

Gurl, Maid said to the sisters,

choosing a card and tossin

she was callin

it poetry

I’m tryna get home

paid time done and feet be achin

and she makin

me stand there and listenin

like she got somethin

and

Maid’s cig moved from lip to hand for the

spinnin of a

Nordic-mocking recitation

Exactly do they do

First exactly.

Exactly do they do.

First exactly.

Maid now hollerin

because sisters

standin

jumpin

bendin

slappin

on knees and backs

the funny too strong and

laughter too big to do it just sittin

And first exactly.

Exactly do they do.

And first exactly and exactly.

And do they do.

And shee-bee-bop dippity doo

Gurl, Maid said shoutin

over the shared laughin

Ella oughta slap that woman for stealin

good music

and calling it poetry

all she doin

is scat. actin smart but just bullshit spittin.

Cards slappin

bids winnin

points addin

winners braggin

losers moanin

all still chucklin.

I thought, Maid said, wheezin

I thought, Baby, you need to get off

that stuff. Sisters

still laughin

denyin

cryin

yessin

and amenin

But I said, Maid said,

in perfect Nordic form,

I said it sounded important

and made my eyes wide

because ya’ll know I ain’t tryin

to be losin that one good job.

Sisters dealin

mmmhmm’n

noddin

with understandin

Another maid,

a sister at the table

of the washerwomen

spoke up, sighin

I sure hope Langston’s right.

The table be quietin,

settlin

calmin

respectin

the recitation

of Prophet Hughes’ intention

“We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.”

Adopted Guest

Friends, I watch your family from the inside out, absorbed.

Here, there are no sneers for children because they exist.

Instead the grownups chat together like a deep breath

No pressure.

Here, the mothers do not pinch your psyche like wet dough and twist

And the fathers do not sit angrily behind

Upright embalming slabs which chill you

Even in passing.

And your family does not indenture me for

Kitchen duty and holding their blame

And you ask me—don’t order me and you don’t get cruel

When I reach demands.

And dishes stay on tables not flung

And laughter is not biting in at my expense

And you go together not make me go in your stead

And I’m asking myself

WTF?

Karla Johnson is a perpetual graduate student, with master’s degrees from both Denver Seminary and the University of Denver. She is a third-generation native of Colorado and counts her grown two sons as her wildest blessings.

Marcia Jones

Car Wash Lullaby

Crystal rain tadpoles twist

upstream, then downstream,

against my windshield.

They curl, sensuous,

all the while watching me

unwind behind

my steering wheel.

Soft suds embrace

the last languid tadpoles

who didn’t escape

in the warning sprinkles.

Bubbles fizzle my car,

hush me in white.

Reclining inside,

I’m on Jupiter

deep in a marble crater

swathed in solitude

and eerie soap clouds,

a lull before the deluge.

Sudden rush, and elegant drops

drum a staccato of silence.

Silver monsoon meditation

washes worry away.

Could death be like this?

At last, more crystal tadpoles

glide forever downstream,

sparkling under crystal parachutes

in the rinse of letting go.

Moonlight Sonata

Wrapped in tangled bedsheets,

tossed and sleepless, she wanders

alone into the night woods.

The first floating notes in C# minor

summon her to still-warm shadows,

restless under the forest canopy.

An ancient square piano ascends

among soaring trees, its burnished body

formed in the forest, from the forest.

Its open lid reflects slender strands

of blue moonlight, its belly brims

with ferns and wild vines.

A flock of nightingales, mysterious

musicians of the dark, slow dances

on worn black and white keys

awakening long-silent notes in an aching

rhythm of tension and release, at once

desperate and joyful—a sonata of healing.

Marcia Jones’s poems won awards at national and state levels through the National Federation of State Poetry Societies (NFSPS). Her poems have appeared in two anthologies: A Flight of Poems (Colorado foothills poets) and All the Lives We’ve Ever Known (Lighthouse Writers). She published her first poetry collection, Only Time, in 2019. Her second collection, Blue Hour, will be out in 2023. She lives in Evergreen, Colorado, where the Rocky Mountains inspire her.

Donald Levering

Song of the Carpet Moths

(Man-Moth) regards it as disease he has inherited susceptibility to.

—Elizabeth Bishop

Hearing voices from the wall,

Man-Moth fears he’s gone insane.

Then he reasons such high vibrations

could be the sonar-seek of bats outside

or emanations from a power line.

He reaches up to tweak

the buds of his antennae, and lo,

the signal strengthens, leading him

to the hanging Navajo weaving.

As he moves closer, the signals

resolve to song. Ah ha,

it’s my little cousin carpet moths.

Give me darkness give me dust

and a niche in a slumbering rug

Give me flecks of dried sheep dung

and globules of lanolin

Give me cochineal dye

that turns the wool the same Ganado red

my tiny tongue and feet become

Give me labyrinth of pattern

to chew down to the weft

the dizziness of Whirling Logs

dazzling Crystal and Spider Web

Two Grey Hills interlocking crosses

I love to inch along the pictures

of Yei giants and pollinating corn

munching on these cords of fodder

enough for all my hungry young

The Weight of the Painting

To calculate a price quote for framing, the framer needs to know the weight of the painting.

How could the framer assign grams or ounces to the scintillating effect of the painting’s pastel aura of autumn shrubbery, the way it lifts the viewer off the ground?

See the small building in the background of the painting? How is the painting’s gravitas altered by the addition of this human dwelling? The ochre of adobe is dense with mud’s local lore. How shall he account for the levitation achieved by the roseate tones of sunset reflected in the building’s tiny windows?

Added to the assessment would be the burden of the history of the landscape painting, from the Tang Dynasty’s floaty silk scrolls of misty waterfalls to William Bradford’s scenes of spouting whales and ice-locked schooners, to Helen Frankenthaler’s flattened landscapes of pansies (what is the heft of her petals?). All these scenes behind the painting must be added to its total gravity.

This calculation would be incomplete without the sway of the critics’ weighing in on the painting. Their hot air plus the weight of public opinion may loft the painter to a moon-walk domain of celebrity, or consign her to the lead-footed realm of public indifference.

Nor can the framer ignore the background boulder that seems to lift off the ground. With its luminous lichens, it is as buoyant as if it were afloat in a salty sea.

Luckily, the price does not include the weight of the neural cloud of imagination about the painter as she worked. Like a cumulus cloud of water vapor, this mental image of the painting must weigh hundreds of thousands of tons but must be discounted from the framer’s fee.

In Pastel

After a diptych by Jane Shoenfeld

When you wake you check your fingers to see

if they’ve turned into ten long sticks

of colored chalk as you just dreamed.

Instead of the dream’s sidewalk, the paper

on one side of your easel starts to scintillate

with flecks from your pastel sticks,

colors nearly bright enough to sear

an optic nerve as you sketch a figure

that quickly grows into a woman

whose mane is a spectrum spray,

whose face an electric seraph’s,

whose voice reverberates like hive-thrum.

* * *

On the other panel, Grandfather

Sitka Spruce is lying down.

A trillium blooms from his chin.

Toadstools and lichen claim his face.

Carpenter ants haul his heartwood

to their potlatch. His needles

become banana-slug meal,

his voice, receding thunder.

His supine totem pole is hollowed

into a canoe that glides you back

sadly to your own casketed grandfather

among banks of overpowering mums.

Ghazal

After a watercolor by Susan List

Dusk on the lagoon like a burner’s gas light.

A hermit’s quietude flickers in the last light.

Twilight slides with earth’s rotation into night.

Old heartache turns me toward this “Last Light.”

Magenta spreads through the gloaming firmament.

Bats and moths and swallows stir in the last light.

Trappings come unmoored, habitual views disperse.

Glimpses of infinity scatter in last light.

Loose photon jubilee, cumulus hosannas.

Memory, time, and distance fuse in last light.

Donald’s eyes rise to the fontanelle of sky.

Love of spectrums of the dusk in List’s “Last Light.”

Donald Levering’s 16th poetry book, Breaking Down Familiar, will be released in May of 2022. A previous book, Coltrane’s God, was Runner-Up in the 2016 New England Book Festival contest in poetry. Before that, The Water Leveling with Us placed 2nd in the 2015 National Federation of Press Women Book Award in Creative Verse. He is a former NEA Fellow and won the 2018 Carve magazine contest, the 2017 Tor House Robinson Jeffers Prize, and the 2014 Literal Latté prize. His work has been featured in Garrison Keillor’s Writer’s Almanac podcast.

Jessy Randall

Not Checking Messages

[stolen french fry form*]

Is

it

from not checking

messages that I

feel good?

[* The stolen french fry is a poetry form I invented based on the number of fries I stole from Price Strobridge and Ashley Crockett at the Poetry West Writers Retreat in Crestone, Colorado, May 2015. I made five thefts of fries, stealing first 1, then 1 again, then 3, then 3 again, then 2. The stolen french fry is therefore a five-line poem with word counts of 1, 1, 3, 3, 2. As far as I know, “Not Checking Messages” is the only poem ever written in stolen french fry form, but perhaps that could change.]

Jessy Randall’s poems have appeared in Poetry, Scientific American, and Women’s Review of Books. Her new collection, Mathematics for Ladies: Poems on Women in Science is forthcoming from the University of London in 2022. She is the Curator of Special Collections at Colorado College, and her website is http://bit.ly/JessyRandall.

Tim Raphael

The trouble begins

when I give bunchgrass a sway

or suggest stones kneel at sunrise,

as if they have something to say about this mesa,

its vantage distinct from morning everywhere.

Better I report unadorned the exact angle of the slope,

how it frames the valley below,

allow the fields to be green, leave riotous out.

A valley of green fields is enough.

Except then the mesa rolls from shadow to sun,

blinks itself awake and slips

into its polka dot juniper dress

in time to spot the owlets learning to fly “on owl-silent wings.”

They’ve fledged but not far from the cliff face,

loitering on a dead branch

in sight of the ledge

where they were born.

Not yet horned or hardened,

one stares back at me like a downy moon,

its face ringed in a winter halo of white feathers,

as if a July snow is on the way.

Flecks of bone, like flakes, are scattered below the nest,

the white mandible of a mouse or mole, bits of leg bone and spine,

a tooth. I’ve interrupted something.

Altered it—

two owlets motionless

save the slow swivel of their famous heads.

Harvester ants a few feet away begin their Sisyphean day,

and I’m tempted to describe them as cheerful—

a pep in their steps up their cartoon volcanoes.

But why try to pin a mood on an ant?

The soil softened by heavy dew.

The soil itself more pebble than dirt.

Is your eye drawn like mine to the dark crevices,

a gash of dry streambed running down the slope,

where I almost will a coyote onto the page?

Omitting the distant hum of State Road 75,

I linger instead on the blue of the sky,

leave out the sweat, my skin already wet,

8 AM and the urge to say something,

do something beyond witness.

No, I am not a reliable ally,

I don’t tell it all,

deny you the scent of after-rain,

ignore the stab of goathead.

Today, it’s the absence of swallows and jays,

no bunches of blue birds in the juniper.

No birdsong calling Lightnin’ Hopkins—

Baby please don’t go Baby please don’t go

The blues scale I practice over & over.

Each note in its place, but O, elusive swing,

somewhere out there,

out beyond the metronome,

where every coyote is a gift,

and daybreak’s refrain is here

& gone.

Blue Truck

We know each other first by our dogs—

walking our road, I see Tipsy

the cattle dog, dragging her dead leg

like a grub hoe & I know Stan will appear

in long slow strides, knit cap on cold mornings.

Scout runs ahead in sniffed greeting,

& when Stan pulls even, we trade a few words

about his garlic crop, about Kate & the kids

& keep moving—he east, me west.

Stan’s unwritten list of loss

is longer than mine & includes his wife

Rosemary, whom I never met,

yet he just hauled a Model A back from Nebraska,

convinced he can find a transmission

& get it back on the road.

Kate had only been half joking

about our own dead truck when she told the seller,

We’ll take the house if you throw in the truck,

as if we had a choice,grass hiding

the airless tires of the Dodge,

a ’49 flatbedwith perfect patina

of autumn rust & blue, as if someone

had sanded dead leaves & sky into fender

& door, dignity in the rotted bed boards

& side rails that once held stacks

of apple crates or firewood—the kind of truck

you’d hop in or on if someone was headed to town,

bouncing over the pitted road when

there was still a bar & gas station, maybe

a kid taking a turn at the wheel. Now

the bench seat is all springs but the chrome

is like new, the Art Deco ram on the hood

ready to charge up valley to the snow on Jicarita Peak.

The sign Kate painted & hung at our gate says

Blue Truck, not Blue Truck Farm—

we have less than a hundred whipple beans

in the ground, assorted beds of zinnias

& cosmos, three rows of wine grapes,

a few apple, pear & plum trees, bush cherries,

a lone apricot & only three hens after

I forgot to latch the coop one night.

Farm is a big word when nothing

is sold and what’s canned or put up

doesn’t fill a pantry shelf,

& farmer may require even more—

a few generations buried

in Father Kuppers’ cemetery, callused hands

like Stan’s that no longer crack in the cold,

a knack for knowing whether clouds gathering

in furrowed rows will bring a soaking rain.

this town

this town has everything it has it all this town except curbs

curbs & sidewalks but this town has everything else no curbs like the ones

in the last town with its paved streets & shaded sidewalks & town dogs

on leashes no leashes in this town this town without a police force no police

no movie theater oh & no barber shop no salons for people or dogs

no tourist bureau with directions to the post office or the Battle

of Embudo Pass or the tree where Harbert’s honeybees swarmed last year

no big muddy river that’s the other town this town has hardly stream enough

for beavers & kingfishers who meet on the banks because there’s no convention

center either but this town has icy canyon roads sopapillas & a past like

& unlike your town & the snow is starting to fly & knock down

the last of the cottonwood leaves & this town looks back & ahead but mostly

is busy today with Clarence’s funeral & keeping kindling dry as though this town

is a protest without slogans that fit on banners a treatise of half-baked

tenets & no ultimatum this sawdust-scented town this town with everything

Tim Raphael lives in Northern New Mexico between the Rio Grande Gorge and Sangre de Cristo Mountains with his wife, Kate. They try to lure their three grown children home for hikes and farm chores as often as possible. Tim’s poems have been featured in I-70 Review, Deep Wild Journal, Sky Island Journal, The Fourth River (Tributaries), Windfall, Cirque, Canary, The Timberline Review, Gold Man Review and two Oregon anthologies. He is a graduate of Carleton College.